During the last seven decades, Doha has transformed from a small town to a big modern city. Even today the speed of progress is so fast that neighbourhoods and roads often become unrecognizable to even long-time residents within a few years. One such neighbourhood is Msheireb. This part of Doha, which is one of the oldest, has completely been rebuilt during the last few years and now it is one of the most modern and futuristic areas of the city. However, the subject of this post is not the modern aspects of this wonderful project but something very old. The project includes restoration of four old houses and their integration into the modern landscape.

One of those four houses is Bin Jelmood House. I had some information about this house and was expecting to see the beauty of traditional Qatari architecture and an opportunity to look into life in the past. And I am happy to write that what I found there was much more than my expectations.

Bin Jelmood House is located at 25°17'13.22"N; 51°31'43.39"E, right in the heart of the city. It is a big house, almost rectangular in shape with sides measuring roughly 47 metres x 75 metres. The entire lengths of the house have rooms and verandahs or covered passages along them. I am not sure when was the house constructed, but definitely much before 1942. It has three or four internal courtyards, except the central one, which is also the largest, others are covered and give you a feeling of indoor halls. The entire structure has been beautifully restored, with the use of traditional materials and techniques. Beautiful wooden windows and doors decorate every part of this house. Even the roofs are supported with traditional wooden beams, called Danshal.

Before entering the house let us take a tour of its beautiful surroundings and view from outside.

Before entering the house let us take a tour of its beautiful surroundings and view from outside.

The entrance of the Bin Jelmood House. (21.02.2019.)

A view from the main street, Company House on the right side, and Bin Jelmood on the left. (21.02.2019.)

The entrance. (21.02.2019.)

The southern wall of the house. (21.02.2019.)

An alley between Bin Jelmood house and the Company House. (21.02.2019.)

The southwestern corner of the house. (21.02.2019.)

A door in the western wall. (21.02.2019.)

A view of the northern wall. (21.02.2019.)

The above two pictures are of a big gate on the northern side of the house. This is probably the main entrance of the house, but is closed for the visitors. (21.02.2019.)

Now let us enter the house, and explore its beautiful architecture and the wealth of information it displays. Actually, so much information is given on the information panels that I feel a little need to write anything more about the museum. Yes, a unique museum in this part of the world. A museum about slavery in this region and Qatar in the past.

Bin Jelmood House

Slavery has existed in nearly every part of the world at one time or another. The story told in Bin Jelmood House is part of that long history. It is also part of the less well-known but older story of slavery in the lands around the Indian Ocean, a region where the experience of slavery was different in many ways from the better-known Atlantic Ocean trade.

The Significance of this house

A trader named "Jelmood" ("rock" of "hard man") lived with his family in this house in the mid - twentieth century. Among the goods he bought and sold were enslaved people. Bin Jelmood House is referred to in a manumission statement - a document that legally freed the enslaved persons - recorded by the British Political Agency in Bahrain on December 6, 1942.

The above pictures show a model of the house. (21.02.2019.)

"Freedom is not an attribute specific to just one civilization, but it is a human value, one that I believe is the driving force behind the making of human history."

Her Highness Sheikh Moza Bint Nasser

Establishing a museum on such a complicated and sensitive issue is indeed a very bold initiative. Facing and confronting the ghosts of the past is not easy and only a bold heart and an enlightened mind can take such a step. And the credit goes to Sheikha Moza Bint Nasser, the wife of HH the father Amir, Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Thani and mother of HH the Amir Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Thani.

The entrance of the house. (21.02.2019.)

A room behind the entrance. (21.02.2019.)

The first section of the house is used as the reception area for the visitors. Here the museum staff is available to assist you and to provide you guidance regarding this house. It was originally an open air small courtyard, but now for the convenience of visitors, it is covered and fully air-conditioned. So that even in a hot weather one can stay very comfortable.

As you can see in the pictures below, the whole house has been restored in its original form and you will find beautiful wooden doors and windows in different rooms and lobbies of the house.

It also has a library stacked with books on the subject of slavery in the world and particularly in this region. It is also a good source of information on the history of Qatar and this region.

In the pictures given below, you can see the largest courtyard in the house. It is a vast open area in the middle of this house.

Below are given a few pictures of corridors and verandahs in the house. All are enclosed and air-conditioned for the convenience of the visitors. But the transparent material used does not interfere with the beauty of the house.

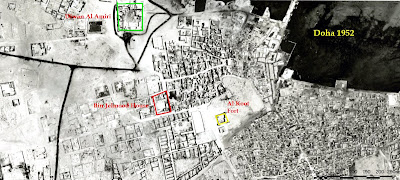

I have taken the three pictures given below from the http://originsofdoha.org/doha/ website. These aerial photographs not only the location of the Jelmood House, but also the dramatic changes took place in Doha city during this period.

Location of Bin Jelmood House in 1947.

Location of Bin Jelmood House in 1952.

Location of Bin Jelmood House in 1959.

The first of the five galleries, informs us about the history of slavery in the world and its ancient roots. Here it is discussed as a global issue and not restriected to a particular area or civilization.

Slavery in the World

Slavery was a system under which people were separated from their kin, forced to work for another person and treated as property to be bought and sold. Enslaved people were held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work or to demand compensation.

People became enslaved througha variety of means. Some were kidnapped, captured as prisoners of war, punished for a crime or tricked into captivity. Others were forced to pay off their own or their relatives' debts. Some people were born into slavery. Abandoned children were taken and enslaved. Some people, with no other means of survival, even gave themselves voluntarily to enslavement. Slavery has affected tens of millions of people throughout hisoty, shaping the political, economic and social structures of civilizations worldwide, from ancient Egypt to medieval Europe and from the Americas to Asia. Slavery is still a global issue.

A view of the first gallery.

Statue of a young Roman slave

"This statue was found in the ancient baths of Aphrodisias in Turkey and dates from the late-second century CE. It demostrates both the taste for the exotic and the popularity of Ethiopian slaves in the Roman Empire. The slave is holding a flask of perfumed oil in his left hand."

West African Manilla

[These bronze or copper bracelets, known as manillas, were worn on the arms by West Africans. Huge quantities were imported from Europe to finance the transatlantic trade.They were used as currency for market purchases, dowries, the payment of fines, and as burial money for the needs of the next world.

Medieval SickesPeasants in medieval Europe were often serfs. These were poor people, obliged by the lord of the manor to work the land they lived on. In return, they were entitled to legal and physical protection and the right to farm certain fields for their own subsistence. Though the lord of the manor and his serfs were bound legally and economically, serfs were not enslaved.

Transatlantic ship slave shacklesOn transatlantic slave ships, captives, taken from Africa, were kept below deck in terrible conditions. Many died in transit from disease. Men, women and children were kept apart. Men were usually handcuffed in pairs by their wrists and with iron leg-rings riveted around their ankles. They normally have so little space that, unable to sit or stand, they could only lie on their sides for the entire 60-day journey.

Aramaic contract for an enslaved girl in Syria (613 BCE)This clay inscription in Aramaic is a slave contract drawn up between a buyer and a seller with witnesses present:Contract concerning a slave girl: Ahi sold a slave for Zakarel. Witnesses: Nabualli, nurse, El'Abad, those are from the merchant Elgabar. Witnesses from Til Abari ... would return a pair of white horses he will give to Sahar and he will be satisfied with it. Deed of Shamashqanah. Date Limu de Sharash-Sharru-Ibnu de Turtanu.]

The second gallery displays the history of slavery in the wider Indian Ocean region, comprising the Middle East, eastern Africa and India.

Slavery in the Indian Ocean World

For centuries, Qatar and the Gulf region have belonged to a trade network that extended across the Indian Ocean. Slavery was a longstanding practice in this expansive region and can be traced as far back as the Sumerian civilization of the third millennium BCE.

Unlike the Atlantic slave trade, slavery in the Indian Ocean World was not limited to a particular race, ethnicity or region. In the Indian Ocean World, people could be enslaved to fill a wide variety of roles. This contrasts with Atlantic trade where most enslaved people worked mainly on the large plantations in Americas.

Sixteenth century map of the Indian Ocean

This map depicts the Indian Ocean, the Gulf, India and North Africa. It was produced around 1519, soon after early Portuguese expeditions began.

Dutch engraved map of the Indian Ocean World, 1705

This map was produced during extensive Dutch colonization and trade with Indonesia and the Indian Ocean World.

Indian Monosson, circa 1850

The favorable wind patterns during the monsoon season made trace activity across the Indian Ocean World possible.

Transporting oxen in Madagascar, 1864

An anonymous English engraving of oxen being shipped from the port of Tamatave, Madagascar, to the islands of Mauritius, and Reunion. These humped cattle called zebe, were transported from the African mainland to Madagascar as early as the eleventh century.

The Indian Ocean World is a large, geographically diverse region that stretches from Africa to the Far East. For centuries, this region was connected by sea trading driven by seasonal monsoons. The Gulf and its largely coastal communities were an important part of the Indian Ocean World. Great civilizations have expanded and extracted across the Indian Ocean World, most notably in India and the Middle East but also in Africa (Abyssinia) and Indonesia (Srivijaya).

Exchange in the Indian Ocean WorldThe Indian Ocean World has a long maritime history, Goods were traded between Africa and the Gulf, India and East Asian and along the maritime Silk Route. The overland Silk Road was one of the most important trade routes in the Indian Ocean World. Silk and other commodities traveled from China o the Mediterranean via the Indian Ocean and the Asian subcontinent. Along with the exchange of goods and technologies, people, both free and enslaved, also moved across this vast region.

Slavery has existed in the Indian Ocean World since ancient times. By comparison, transatlantic slavery is relatively recent, dating back to the sixteenth century. In the transatlantic slave trade, the European powers sourced mostly men from Africa to work on plantations in the Americas. In the Indian Ocean World slave trade, a large number of women and children were enslaved and enslaved people came from many diverse places.

Pre-Islamic Slavery in the Arabian RegionSlavery in the Arabian Region was widely practiced in late-Antiquity and the pre-Islamic period. Enslaved people came from the Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt and Africa (particularly Abyssinia and Nubia). Mecca, Baghdad and Siraf were leading commercial centers and major slave markets. Indigenous Arab populations were enslaved through warfare and tribal conflicts.

Abu Bakr Al SiddiqAbdullah ibn Abi Quhafa, known as Abu Bakr Al Siddiq, was teh first caliph and an important figure in the history of early Islam. He followed the instructions of the Prophet (PBUH) and freed many enslaved people, including Bilal Bin Rabah Al Habashi.

Bilal bin Rabah Al HabashiBilal Bin Rabah Al Habashi (580 - 640 CE) was a manumitted slave and a companion of the Prophet (PBUH). He was emancipated by Abu Bakr Al Siddiq. He became Islam's first muezzin (caller to prayer) and was renowned for the beauty of his voice.

The influence of IslamIslam regulated the institution of slavery, improving the lives of the enslaved through the Quran's teachings and the hadith (the Prophet Muhammad's sayingsb[peace be upon him]). Sharia (law) contains rules governing slavery. Islam prohibited the enslavement of Muslims. It permitted capture in war, purchase and birth into slavery as the only methods of enslaving people. The enslaved were given limited rights in recognition of their humanity. Islam encouraged humane treatment and the freeing of slaves as an act of piety.

The Arabic word for a male enslaved person is 'abd'. While the Quran used the term abd to signify "servant of God" the most common phrase for enslaved persons is "ma malakat aymanukum" (those whom your right hand possess).Quran 4:36

And worship God and do not ascribe any partner to Him. And (show) kindness to parents and kinsfolk and orphans and the needy and to the neighbor who is of your kin and also to the neighbor who is not and to the fellow traveler and to the wayfarer and to those whom your right hands possess.

Bilal Bin Rabah Al Habashi

Bilal Bin Rabah Al Habashi was one of the earliest followers of the Prophet (PBUH) and became his trusted companion. Known as 'the Ethiopian', he was enslaved by Ummayah ibn Khalaf who violently opposed the Prophet (PBUH) and his teachings. When Bilal accepted Islam and insisted there was only one God, he was tortured by ibn Khalaf. When Abu Bakr Al Siddiq heard of Bilal's piety and commitment, he purchased and freed him.

Methods of enslavement

A number of methods were used to enslave people throughout the Indian Ocean World. These included warfare, punishment for crime, raids and kidnapping, indebtedness, the sale of dependents and the exploitation of the destitute.

Warfare:Throughout history, was has resulted in the displacement of peoples. The Indian Ocean World was no exception. For example, the sixteenth-century religious wards between Christian Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) and Muslim Adal-Ifat (a sultanate in eastern Ethiopia and northern Somalia) was an important source of enslaved Africans for the Sultanate of Gujarat. The killing of male captives continued in some regions into the nineteenth century. However, keeping them alive to supply labor became increasingly necessary as farming methods improved crop production, cities expanded and commerce increased.

Stone carving of enslaved people in Angkor, twelfth century

This stone frieze in the Bayon temple at Angkor, Cambodia, depicts war and enslavement.

Destruction of the pirate haunt of Carang on the island of Sulu by HMS Nassau in 1872

In an effort to maintain maritime peace and ensure the safety of the trade routes, European powers regularly undertook military action against known pirates camps in the Sulu archipelago and elsewhere in the Indian Ocean World.

Balani pirates, Philippines, circa 1910

These slave-trading pirates are of Chinese descent. They probably migrated from Singapore to the Sulu archipelago (Philippines) in the late-nineteenth century.

Dayaks slave hunting, circa 1840

Dayaks of Borneo raiding other tribes in pursuit of children to enslave.

Rice farmers in Siam, 1916

Rice sowers toss seed from large baskets onto a flooded rice field. Many Siamese rice farmers worked as covee labor (forced labor as a kind of tax payment) or as slaves until the 1940s when reforms to the rice industry were enacted.

Displacement

Captives were moved by land and sea across the Indian Ocean World. Where a network of slave trade existed, a person could be resold several times during an overland journey.

Enslaved persons were transported in quite small groups. A dhow sailing across the Red Sea or along the East African coast might contain as few as ten enslaved people, along with other traded goods. Dhows capable of carrying dozens or even hundreds of slaves existed but they were rare. The risks to these enslaved people were high and included overcrowding, malnutrition, vulnerability to disease and suicide.

An Arab slave ship in the Red Sea, 1874

An Arab slave ship in the Red Sea, with a British cruiser in sight, 1874. A report from the British Anti-Slavery Society of 1890 states that the journey across the Red Sea is from 6 - 12 hours - the slaves are embarked on any craft, take only a few moments to be packed on board and the dhows run straight for the Arabian coast.

Arab slave market, Yemen, 1237 CE.

Illustration of a slave market in Yemen, thirteenth century, from Al Maqamat Al Hariri

A scene depicting the slave being transported overland.

Slaves busy in their daily lives.

In the Indian Ocean World, the distinction between enslaved and free people was often blurred. Enslaved people in early Islamic Arabia were considered part of the family, though of lower status to free family members. Children born to enslaved women taken as wives (suria) were considered free. Some enslaved individuals attained prominent positions. Examples include Zayd ibn Haritha, a general and confidant of the prophet (PBUH), and Bilal bin Rabah Al Habashi, one of the earliest believers in Islam and a companion of the prophet (PBUH). Some enslaved males, recruited as soldiers in the army, attained considerable influence in successive Muslim caliphates and even seized power. The most famous enslaved soldiers were the Mamluks who established their own caliphates in Egypt and Syria.

Enslavement was not linked to any particular race, ethnicity or religious background. Although enslaved Africans had a long history in Arabia, until the eighteenth century most enslaved people in the region came from Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Persia. This enslaved 'white' population, known as Saqaliba, played a major role in various Muslim caliphates.

Some free people could have living conditions and status inferior to those of the enslaved. In the Indian Ocean World societies, the enslaved and their owners depended upon each other. Living in bondage could sometime be an advantage and provide slaves protection from destitution.

Roles of the Enslaved

In the Indian Ocean World, enslaved men and women undertook a far wider range of tasks and responsibilities than they did in the transatlantic world.

For instance, the courts and houses of nobility throughout the Abbasid, Moghul and Ottoman empires employed female slaves as suria in harems presided over by emasculated male slaves (eunuchs) and as qiyans (singers and court entertainers). Males slaves were employed as administrative servants and guards, and both males and females performed domestic duties.

Umayyad mosque and palace, Damascus, seventeenth century

The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs became known for their opulence which included the acquisition of large numbers of domestic servants. The palace of the Abbasid caliph al-Muktafi Billah (902-908 CE) had 10,000 enslaved people, including black Africans and Saqaliba (white) enslaved persons.

Signs of wealth

In the high society of more developed Indian Ocean World communities, enslaved people were symbols of "conspicuous consumption" - put on public display to demonstrate the power and wealth of their owner. This was often the case in the Islamic caliphates which expanded from the Arabian Peninsula across southeastern Europe, North Africa and the India Ocean World between the seventh and twelfth centuries.

Arab sharif with slave, 1880

This photograph indicates how enslaved people adopted the dress and customs of their Arabian masters. Also note that the enslaved man (pictured on the right) is armed with a short sword attached to his waist.

Arab merchant from Mecca with his Circassian slave, 1880s

The central European regions of Caucasus, Balkans and Circassia were the principal sources of enslavement for the Arab region until the mid-nineteenth century.

Servant and eunuch with master's child

Photograph from Christian Snouk's study of Mecca, published in 1888.

Illustration of women sitting on a terrace. Mughal School, seventeenth century

The courts of the Mughal emperors contained the emperor's wives, enslaved wives (suria), ladies-in-waiting, enslaved girls servants, female officials and the enuchs who guarded them.

The Kislar Agassi, eighteenth century illustration

The Kislar Agassi was the commandant of the corps of eunuchs guards and ranked next to the grand vizier and the chief mufti. Kislar Agassi means guardian of the damsels.

African musicians, Mecca, 1888-89

This illustration comes from Christian Snouk's book Mecca, published in the Netherlands between 1888 and 1889. In the book, Snouk comments, there is a preference for Abyssinians, who have many good qualities and abound of all shades from light yellow to dark brown. Circassian are little valued on account of their enormous pretensions ... more important as workers, are the African slaves. They come mostly from the Soudan, and are set to the heavier tasks of building, quarrying ...

Turkiyyeh, a Circassian slave (1914)

Turkiyyeh was a Circassian enslaved in Saudi Arabia. She was a gift from the sultan to one Mohammad Al Rasheed. Ownership of enslaved people was not restricted to wealthy and powerful. In Arabia, ordinary domestic households might own one to two enslaved persons, usually employed as domestic servants or suria, enslaved wives. In many places, those freed from enslavement aspired to owning slaves of their own.

Dancers serving wine, Samarra

This ninth-century image comes from the ancient city of Samarra, then capital of the Abbasid Empire.

Mamluks and Janissaries

The Islamic caliphates employed armies of enslaved men to expand and maintain order in their territories. In the ninth century, the Abbasid Empire formed an army comprised of enslaved men recruited at an early age mostly from the Balkan and Caucasus regions of Europe but also from Africa. This Mamluk army became an important military force during the Ayyubid dynasty of the twelfth century in Egypt. Mamluk soldiers were manumitted by their masters at the end of their training period and were then in a position to become powerful citizens in Islamic society. Some even became rulers. The Mamluks established their own caliphates and defended Islamic territories by expelling the Crusaders and defeating the Moguls.

Similarly, in the later Ottoman Empire, young men were forcibly recruited to the army from Balkans and Caucasus in what was called the devshirme system. Devshirme was the practice by which boys, known as Janissaries, were taken from Christian families bu skilled scouts and trained in religious and military institutions.

Plantation Work

Extensive agricultural production became increasingly common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with the growing global demand for products such as rice, sago, cloves and rubber. By the mid-nineteenth century, a plantation system had developed in the East African region around Zanzibar where goods such as cloves were grown for a global market. In the nineteenth century, as estimated 1.6 million people were enslaved in East Africa. Half this number remained on the continent to work on the plantations while the other half was displaced across the Indian Ocean World, including the Gulf region.

Few Indian Ocean World plantations matched those of the transatlantic in size. Plantation labor in the Indian Ocean World tended to consist of indentured servants who worked for a fixed period in exchange for food, clothing and lodging, rather than as chattel (owned property) slaves. When the enslaved were employed in Indian Ocean World agriculture, it was often on small projects alongside peasant farmers.

A Janissary officer practicing devshirme for Sultan Suleyman

A Janissary officer practicing devshirme for Sultan Suleyman I (1495 - 1566), from Suelamannme, 1558.

Mamluk archer

Illustration of a Mamluk mounted archer, fourteenth century.

Clove plantation, Zanzibar, nineteenth century

Laborers arriving into Mauritius, 1842.

A group of laborers called 'hill coolies', landing at the colony of Mauritius in 1842. They were imported to work for merchants and sugar planters. Though the indentured system was not strictly slavery, the Illustrated London News at the time commented that it was near to it since it led to similar human grievances. One in Mauritius, the laborers had few rights of redress aginst their employers.

Violence

Enslaved persons acquired through war or in raids suffered physical violence and emotional torment from the moment of their capture.

The degree of violence suffered by victim differed widely. Some masters treated their slaves benevolently while others were extremely harsh. Those who held positions of status or worked alongside their masters were generally considered too useful and valuable to be treated badly.

The arrival of Islam had a positive influence on the way enslaved people were treatedas it advocated kindness and encouraged manumission.

Photograph of Tippu Tip, nineteenth century

Tippu Tip (Arabic name: Hamed bin Muhammed Al Murjebi) was a Swahili-Zanzibari ivory trader and clove-plantation owner who also captured and traded in enslaved people. He was employed by King of Leopold of Belgium as a regional authority in the Congo Free State. He also had claims to an elite Omani family on his mother's side.

Tippu Tip with enslaved group, around 1890

Tip was reputed to have owned some 10,000 enslaved people and seven plantations.

Slave dealers and enslaved group, Zanzibar

Illustration of a street scene in Zanzibar which appeared in the British newspaper The Graphic in 1873. It shows chained enslaved people standing in line as merchants negotiate prices for them.

Photograph of a child in chains, Zanzibar, nineteenth century

The most frequent form of violence was physical restraint. In this example, a child is shackled by the foot and carries a wooden block on his head.

Bahram Gur

In a story from the Shahnameh, the Persian King, Bahram Gur, sat astride his horse as it trampled to death Azada, his favorite slave, because she did not praise his hunting skills highly enough. The story illustrates how precarious life was for enslaved people.

Family integration

For most enslaved people, security, food and shelter, rather than liberty, were life's primary concerns. These could be more easily attained if slaves became part of their surrounding society. Women, who represented two-thirds of enslaved people in the Indian Ocean World, often integrated so that they could provide security and a better life for themselves and their children. They could achieve this if they could bear their master a child. Integration into Gulf society was also made easier by learning to speak the same language and practicing the same religion as the host society.

Conditions for integration

The extent to which enslaved people could become part of their new society on depended on:

- The ethnicity of the enslaved person.

- The degree of contrast between their home society and their new surroundings.

- Their master's religion: If a master was Muslim, enslaved people would often accept Islam and could sometimes be manumitted as a result.

- Their placement: Those operating as individuals or in small groups had greater opportunities for integration than those in large groups.

- The prospect of living or working alongside their masters.

- The ability to learn new languages and absorb new beliefs and traditions: In particular children often forgot their original language and place of birth.

Bowl depicting Bahram Gur and enslaved servant (late twelfth to early thirteenth century )

Bahram Gur astride his horse as it trampled Azada.

Photograph of Arabs of African descent in Muscat, early twntieth-century.

Men in Arab dress in Zanzibar, early twentieth century

From the eighteenth century onwards, trade between East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula increased. In 1841, the Sultan of Muscat moved his court of Zanzibar, which resulted in a long period of exchange between the two places. This photograph illustrates the cultural currents that flowed between Muscat and Zanzibar.

Swahili women in Arabic costume, Tanzania

East Africa has been part of the Muslim Indian Ocean World for centuries. Its societies are a mix of Arab - African cultures. The term Swahili comes from the Arabic word for "'coasts" (Swahil). The Swahili language (Kiswahili), which incorporates elements of Arabic, Persian, Portuguese and English, is a Bantu language spoken by various ethnic groups in much of Eastern Africa.

Lack of group consciousness

East Africa has been part of the Muslim Indian Ocean World for centuries. Its societies are a mix of Arab-African cultures. The term Swahili from the Arabic word for "coasts" (Sawahil). The Swahili language (Kiswahili), which incorporates elements of Arabic, Persian, Portuguese and English, is a Bantu language spoken by various ethnic groups in much of Eastern Africa.

The third gallery is about slavery in Qatar. It is very interesting, as it not only tells us about the slavery in Qatar but also the society, culture and political conditions about a century ago.

Introduction

In the five rooms that lead off this colonnade, our story shifts from the wider Indian Ocean world to focus specifically on slavery in Qatar.

In the first room we set the scene, describing Qatar in the early decades of the twentieth century when the numbers of enslaved people were the highest. In the second, we discover where enslaved people came from. The third room describes the transport and sale of the enslaved who were traded in markets along the land and sea trade routes to Qatar. The final two rooms explore the work and daily lives of Qatar's enslaved people.

These settings reveal the circumstances of the enslaved people whose lives form part of the story of this country. We encourage you to explore them.

Photograph of the Doha landscape, Herman Burchardt, 1904

Aerial photograph of Doha, 1947.

Qatar as a political entity

Qatar emerged as a political entity in 1868 after Sheikh Mohammed bin Thani signed a protection treaty with the British Political Resident in Gulf.The British and the Ottoman Turks showed little interest in Qatar the latter half of the nineteenth century. In 1872, the Turks set up a military garrison in Doha which stayed in place until First World War. After their departure in 1916, the British maintained a degree of political influence over Qatar from their base in Bahrain. The British did not establish a political residency in Qatar until 1949.

Integration of Qatar into the global economy

The increase in enslaved labor in the Gulf was closely connected to the rise in demand for labor on the African east coast. Most of the Middle East, including the Gulf, was drawn into an expanding global economy from the nineteenth century onwards. This generated economic growth in some sectors. A few people became wealthy. The world was demanding pearls which Qatar had in plentiful supply. During this period, the pearling industry was the principal employer of enslaved workers in Qatar.

Turkish military fort, Doha, 1904.

Turkish soldiers, Doha, 1904

An Ottoman force first landed in Doha in 1871. In 1872, Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani reluctantly agreed to Ottoman sovereignty in Qatar.

Maharajah Bhupinder Singh, twentieth century

Photograph of Maharajah Bhupinder Singh in pearls, twentieth century.

Palmers biscuit advert

Advertisement for Palmer's biscuits, around 1925, depicting a woman in pearls.

Sources of enslaved people

For many centuries, the major sources of enslaved people in Arabia were northeast Africa and the Sahel region of central and western Africa. Muslim pilgrims were particularly vulnerable to being captured and enslaved as they made the long and difficult journey from the African interior to Mecca.

By the late nineteenth century, those enslaved in Qatar were mostly from East Africa and the Red Sea area. Thousands of victims were marched to the coast and then shipped to Zanzibar to be auctioned and transported to further destinations. Dhows travelled up the Indian Ocean coast to ports such as Sur and Wudum in Oman. Some of the enslaved were brought to Qatar. Enslaved people also came from the Horn of Africa and Yemen.

In the early twentieth century, fewer enslaved people arrived from East Africa and the Red Sea partly because of anti slavery measures being conducted along East African and Arabian shores. Dealers in the slave trade instead turned their attention to Baluchistan where destitution was forcing people into slavery.

Shadings show major slavery sources for Qatar in the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries - East Africa, Northeast Africa and Baluchistan.

Abyssinian coastline, 1832

Enslaved Ethiopians were exported from ports such as Massawa and Assab.

Baluchistan

Western Baluchistan was conquered by Persia in the nineteenth century. Its boundary was fixed in 1871. Eastern Baluchistan was under Omani influence based in the port city of Gwadar. In the early twentieth century and particularly in the years surrounding the First World War, Baluchistan was hit hard by famine and disease. Great numbers of people were forced into desperate poverty. The entire Western Indian Ocean region was affected by disruption of food supplies, disease (a consequence of troop movements and the Hajj pilgrimage), famine and changes in climate.

Some Baluchis were enslaved, though in relatively small numbers when compared to earlier East African trade. The Khans (Persian tribal chiefs) were largely responsible for this trade and tended either to kidnap people or offer them false jobs in the Gulf. In a destitute region stricken by poverty and hunger, some preffered the security of slavery to the hardships of freedom and sold themselves willingly to caravans bound for Buraimi. Some of these people were brought to Qatar.

Bolan Pass, Baluchistan, 1885

A camel caravan travels along the pass between Sibi and Quetta in Baluchistan.

Gwadar, Baluchistan, 1838

Tribal family, Baluchistan, 1910

Born into slavery

Manumission records from Bahrain tell us that a significant proportion of slaves seeking release had lived all their lives in slavery. They had been born into slavery in Qatar or elsewhere in the Gulf region. These statements also indicate that masters frequently gave them spouses, thereby ensuring that their numbers remained steady.

From the manumission statements:

Atiyah, about 30 in 1944, stated, I was brought in Ibrahim's house, where I was married to Ibrahim's slave named Somaiman.

Mubarak, about 34 in 1945, was born into slavery. He stated that his father, Marzook, was the slave of Ali of Doha. My mother, Zehra, slave of Hasan of Khor.

Zayid, about 23 in 1945, stated, I am a born slave. My father, Joher, and mother, Fidhah, were the slaves of Ahmed of Qatar.

Mubarak, about 25, in 1945, stated, I am a born slave from slave parents of Dohah, Qatar.

Effect of slavery on East Africa.

The large scale raiding in East Africa during the nineteenth century disrupted families and communities and contributed to destabilization in the region. With the rise of a large commercial slave trade, enslaving one's enemy provided more reason to go to war.

Some East African entrepreneurs became wealthy by exploiting slave labor on coastal plantations. Zanzibar's sultan profited from a tax on slave sales.

Transport and sale

Enslaved persons were brought to the Gulf via land and sea routes. By the early twentieth century, 2,000 to 3,000 enslaved people were imported annually into the Gulf. Most of them first arrived in Oman and were then sent by small boats to markets further north, particularly to the region's largest pearling fleets in Bahrain, the UAE and Qatar.

Capture

Kidnapping and reading were common. People were sold into slavery to pay off debts, enslaved as punishment for offenses or were captured in wars. In the mid twentieth century, the use of firearms in the capturing of slaves became common.

Statements by British officers on naval ships off the Arabian coast in 1869 offer insight into methods of capture:

Male slave, name, Marazuku; tribe, Wyassa; age, about 25. He was stolen while asleep in his village near Lake Nyassa, by Arabs and taken to Kilwa where he remained for two months. He was then sent to Zanzibar where he stayed for four months. He was finally sold and shipped to Muscat. He has a sister in Zanzibar who had been sold to Arabs by her father.

Male slave, name, Hamis, Wyassa tribe, age, about 20. He was taken prisoner in a fight between Wyassa and Wahiyou and taken to Uhiyou country. He was sold to an Arab and taken down to Kilwa, remaining two days. He was taken to Zanzibar where he lived for two months. He was then sold and and shipped to Muscat. He states that the dhow took 20 days to go from Zanzibar ro Brava where he stayed for five (days). It took six (days) from Brava to Ras Madraka.

Overland journey

From their place of capture, victims were chained or roped together in convoys and marched to the coast. These overland journeys could take weeks or even months. These captives could be bought, sold and resold at trading posts along the way. Most of the enslaved people sold on the coast of East Africa taken to the post city of Kilwa on the southern coast of today's Tanzania. They came from southern Tanzania, norhtern Mozambique, Malwai, eastern Congo and nothern Zambia.

People captured in the area east of Lake Tanganyika (in current day Congo) walked up to 1,000 miles to the coast. They suffered hunger and thirst and were vulnerable to disease. They could also be recaptured or killed by marauding gangs. Overland marches, during which high numbers of victims died, were arduous and inhumane.

The captured who were taken to Kilwa might stay there for periods as short as a few days or as long as several years. The length of stay depended on whether they were employed at plantations. If they were exported to the Gulf and Yemen, they would have to wait for the seasonal monsoons to pass before it was safe to travel up the East African coast.

Illustration of an African slave caravan, by Eduouard Riou, 1861

Enslaved convoy being transported, Zanzibar (nineteenth century)

Enslaved convoy chained together, Zanzibar (nineteenth century)

Sea Journey

All those enslaved from East Africa and Baluchistan made part of the journey by sea. Their numbers and treatment varied considerably. Occasinally, scores were transported on a single dhow from Zanzibar or Pemba. Journeys could last 30 days. They were packed into ship's hull and chained to shelves of bamboo, existing on nothing more than a daily ration of half a coconut shell of water and a handful of rice or dried shark meat. It disease broke out, fatalities would be high.

More commonly, traders moved the enslaved in small numbers and over short journeys that lasted only hours. The captured were carried on top of cargo such as mangrove poles and ivory.

In the 1870s, the British observer George Sulivan noted that few of the dhows he encountered were fitted with tanks. planks and shackles required for mass transit and that many of the enslaved were healthy. His figures suggest an average of 20 people per dhow.

The enslaved rarely made much of a ship's cargo. Individual owner or traders transported them in small groups they could supervise. They also sent them in the care of a ship's captain, paying an extra fee for transit costs.

Prices of slaves are given in Indian Rupees.

Domestic servitude

In the early twentieth century, many enslaved people filled domestic roles in Qatar. They worked not only in larger settlements of Doha and Al Wakra but also in the sparsely populated northern parts of the country. Compensation records from 1952 suggest that many families in this area owned one or two enslaved workers.

In a land and period of few material resources, possession of enslaved workers meant having someone with whom to share the workload. For a very few, it represented economic advantage and a display of wealth.

The enslaved in Qatar often lived closely with the families they served. Masters were obliged to feed, clothe and house their slaves. In a middle-class household, an enslaved person was, in many respect, treated as one of the family, eating the same food, wearing similar clothes and sharing in the family' daily life. However, knowing that they could be sold with little notice was a constant concern. The fear of separation was sometimes made worse by close ties between the slave and the household.

Daily labor

Both male and female enslaved people in Qatar carried out domestic labor, generally fetching water and firewood. Outside the pearling season, men constructed houses, herded camels and broke stone. These tasks could be long and arduous. Firewood was collected from far away and carried back to the house by donkey. Some would have had to walk a long way to fetch water from wells. Enslaved men also served as guards in the households of the ruling families.

Enslaved females prepared food and provided childcare. In some houses they were kept as suria. The relative poverty of Qataris and the country's harsh climate could make daily life an arduous routine for both the enslaved and the families they served.

Filling water skins at Salwa wells, c 1921

Women washing clothes at Al Khor seashore, c 1940s

Photograph of water being drawn at a well, Qatar, early-twentieth century

Social acculturation

Because those enslaved were non-Muslims, their acceptance of Islam was an important element of social integration. Those born into slavery could be Muslim but because their parents were enslaved they inherited their parents' enslaved status.

Before arriving in Qatar, newly imported enslaved people were often held on the Omani coast. Here they would learn their duties and the Arabic language so as to prepare them for sale to potential owners. Nearly all those who received manumission certificates at British consulates and agencies in the Gulf between 1907 and 1940 said they had spent at least three years in Oman before being sold to masters from Gulf countries such as Qatar.

Cultural Survival

Enslaved person often practiced their original cultural traditions in private. An example of this is the zar-bori spirit-possession ritual. Zar was performed in West Africa, Sudan, Somalia, Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco, it spread to the Gulf through slave trade, the natural migration of people and the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj).

The zar-bori, tanbura and laywa rituals were performed for the purpose of healing physical and mental illnesses. It also allowed people to express their feelings and helped them to cope with the oppression of slavery and hardship.

The enslaved who practiced these rituals would wait until they had observed evening prayers with their owners. When the master was asleep, they would sneak out of the house to the tanbura or laywa performance. Belief in spirit possession in the Gulf is testimony to the resilience of African cultural traditions in the region.

Slavery in modern pearling and date cultivation

From 1879 to 1929, the Gulf's pearling industry, which previously produced only for regional markets, was opened up to the growing global demand for pearls. One observer wrote:

The pearl fishery, of which these islands (Bahrain and Qatar) form the centre, is calculated to yield annually about twenty lacks of rupees worth for exportation, the greatest proportion of which find their way to India, and the remainder are dispersed throughout the Persian and Turkish empires, by way of Bushire, Bussorah and Baghdad, and from thence to Constantinople, Syria, Egypt and even as far as the great capitals of Europe.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the Gulf was producing more pearls by value than all other parts of the world combined.

Another Gulf product, dates, also found global appeal around the same time. During the boom in these industries, the demand for imported enslaved labor increased substantially.

Pearl Diving

In summer, pearling dhows would sail along Qatar's oyster banks. Once a boat arrived at a promising spot, it would anchor and the crew was divided into groups. Some dived while others hauled up the divers and received the oysters.

A small basket, which held eight to ten oysters, was suspended from the diver's neck. He would place his feet on a stone attached to a cord, inhale deeply and raised his right arm as a signal. He would be lowered to a depth of between 9 to 27 meters. He would then swim along the sea floor, collecting as many oysters as he could gather. Some divers could remain underwater as long as 90 seconds and dive up to 50 times a day. On jerking the line, the diver would be hauled to the surface.

The oysters were opened with a clasp knife on deck and the pearls removed. Pearlers worked from sunrise to sunset.

Photograph of Qatari divers preparing to dive, around 1930

Fishing for pearls in the Gulf, 1870

Pearling and indentured servitude

Not all divers were enslaved. Arabs, free Africans and Baluchis joined their ranks. Both free and enslaved divers worked side by side and were dependent on each other for their survival.

While free divers kept the proceeds from each pearl season, enslaved divers surrendered their earnings to their maters. But free divers were also exploited. Pearling captains and merchant-boat owners controlled them through a credit system. Sometimes forced to borrow at high interest themselves, they gave loans in excess of the free divers' earnings. This ensured that these divers' services were retained year after year. Divers were paid in rice and other staples from a company store, another source of profit for captains and merchants. Since most divers were illiterate some captains and boat owners found it easy to falsify written records of debts to enhance their profits.

The collapse of pearling

The global economic depression of the 1930s had a disastrous effect on Qatar. Because pearls were the country's principal export, decreased demand meant an end for pearl diving. Everyone connected to pearling suffered. The decline was hastened by the cultivation and distribution of Japanese cultured pearls during this time.

The rapid falling off of the Gulf's pearl and date industries virtually ruined its economy. As revenues declines, abuse by masters often increased. The numbers of enslaved people running away increased, as did the manumission of slaves by their masters who could no longer afford to shelter and feed them.

Woman sorting pearls by size, Japanese oyster farm, 1947

Opening the oysters on deck, 1930

Workers at a cultured far, Japan, 1947

Crisis and opportunity for Qatar's enslaved

A group of oil workers in front of a large crane, early 1950s

Lives of the enslaved

An enslaved persons' prospects were in the hands of his or her master. For some, ill-treatment made escape a worthwhile gamble. Manumission was uncommon and opportunities to gain freedom were scarce. Even if it was granted, freedom was a mixed blessing as it did not always bring improvement in living conditions.

The Fourth Gallery shows the efforts made to end slavery in Qatar and the integration of former slaves in the society as free and equal citizens of Qatar. It shows a happy ending to a tragic story.

This gallery explores the experiences of those enslaved in Qatar. These are divided into:

- Integration into the family

- Freedom through manumission granted by one's master or colonial official

- Freedom through Qatar's abolition of slavery

Integration into the family

Many of the enslaved in Qatar were treated like family members and found contentment living with their master's family. In addition to the personal bonds that might have developed, this arrangement meant that enslaved people were provided with food and shelter and may have enjoyed a better standard of living than if fending for themselves. Given the low numbers that sought escape and manumission, integration was probably a common experience. This theory is difficult to confirm as there were significant risks involved in running away.

The observation of George Maxwell, a British chief secretary of the Malay states, bears this out:

In a middle-class house in the towns, a slave is generally treated as one of the family, eating the same food, wearing similar clothes, and, for better or for worse, sharing the family's fortunes. Aside from the ever-present threat of rupture through sale, the lives of slaves were very similar to free Qataris.

An extract from a letter written by a political officer in Qatar on April 14, 1952, makes similar comments:

Many slaves will of course remain with their former owners, some from choice, some, chiefly concubines, from necessity. The former will be able to insist on receiving wages for their service, but those who are dependent on their masters for their keep and that of their family cannot be expected to change their servile status if if they have no alternative livelihood.

Manumission by slave masters

The most common form of manumission was that granted by masters according to Islamic tradition. A master might manumit an enslaved person:

- If the felt that the enslaved person had distinguished him or herself and deserved freedom.

- If the enslaved person was able to buy freedom through payment or paying off a debt.

- If the master had mistreated the enslaved person of committed immoral acts.

- If an enslaved woman and given birth to the master's child.

- As a pious gesture by the master before his death.

- In celebration of the master's safe return from Hajj.

Escape and Manumission

Manumission records list many reasons why enslaved people sought to escape their masters. Ill-treatment (such as inadequate provision of clothing and food), confiscation of money, beatings or other forms of violence or prospect of being sold all feature prominently. However, the number of those attempting escape was small in relation to the estimated total number of enslaved people in Qatar.

The best prospect of freedom was to flee to the British Political Agency in nearby Bahrain where slavery had already been abolished. There, enslaved people could request a hearing. Each case for manumission was considered separately. Manumitted slaves were given certificates as proof of their freedom which allowed them, in theory, to return to Qatar without fear of their liberty being disregarded by their previous owner or another aspiring master.

Group of enslaved children, possibly in Aden, around 1890

Aden was a British possession in southwestern Arabia. It was a convenient place for the disembarkation of rescued enslaved people.

East African enslaved group, HMS Daphne, 1868

East African enslaved people taken aboard HMS Daphne from a dhow, November 1868.

British illustrated Press: A dhow episode, 1893.

A Dhow Episode: The capture of a slaver off the east coast Africa, and the agency that settled the freed slaves in life. This rare depiction of chattel slaves after their release was published in The Graphic, June 10, 1893.

British sailors boarding a slave dhow, around 1885

An unusual image of British sailors boarding and Arab dhow during an anti-slavery patrol off the East African coast, circa 1885.

East African slaves, HMS Daphne, 1868

British naval patrol

While Britain abolished slavery in 1833, it had ended trading in slaves in 1807 and used its formidable naval power to discourage other nations from slave trading.

Britain wanted to secure the Gulf. It was an important channel of communication and trade between Britain, Bushire (Persia) and India. The British offered the Gulf sheikhdoms protection in exchange for their outlawing of piracy and the slave trade. As an extension of this effort, Britain concluded treaties with the Sultan of Zanzibar that allowed inspection of ships in the waters under his jurisdiction.

Rescue and abandonment

In the late nineteenth century, the British Navy's efforts to suppress the Gulf slave trade were publicized dramatically illustrated newspaper accounts and books in Britain. These stories focused on Zanzibar and its export of enslaved people to the Gulf region.

The articles described the British Navy's interception of Arab dhows, the enslaved cargo found on board, and their rescue and landing at ports under British protection. However, once the photographs had been staged, the rescued were often abandoned. British ship captains were reportedly instructed to offload enslaved people unless their lives were in danger if they remained on board the dhow.

Those who were rescued were taken to either Aden Bombay-British-controlled ports. Many of the rescued suffered health problems and died early deaths. In 1871, Bishop William Tozer of Zanzibar estimated that of the 3,000 or more Africans rescued from dhows and taken to Aden between 1865 and 1869, over 1,000 had died within five years. Col. Robert Lambert Playfair also noted that, in his experience, those rescued and landed at Aden were decimated within a year. All had died from the same cause - disease of the lungs.

Manumission statements

These documents, which included manumission statements and related correspondence, give insight into the circumstances of enslaved people seeking manumission during this time.

Statement of Faraj bin Razi aged about 50 recorded on the 31st May 1927.

I beg to state that I am born in Abysinia and while I was a young boy I was stolen by Arab slave-traders and was brought to Mecca and at this town I was sold to my master's father Muhammad Abdul Wahab a pearl merchant of Darin in the district of Qatif. I was about ten years old when I was brought by my master to Darin and have ever since served him as a faithful slave. I was employed by him as a diver during the summer and used to build houses for him in the winter season. My master's father Muhammad bin Abdul Wahab gave me a negress in marriage and I with my wife served them in their houes as slaves.

My wife is named Ruqiah daughter of Sultan ________ and she gave birth to five male children and two female ones. They are named as under:-

(1) ________________ (2) ________________ (3) ________________

(4) ________________ (5) ________________ (6) ________________ (7) ________________

During his father's lifetime my master did not live in Darin as his father did not like he was staying in Qatar but a year prior to his father's death he came to Darin and went to Bombay where his father had gone for medical treatment and after his father breathed his last he came back to Darin.

Jassim did not treat me and my children as a good master he used to employ us all in hard work and nevertheless he would not give us an adequate maintenance and would maltreat us. He was very niggardly as regard our food and raiment. He would never show us any kindness. Righteous persons in Darin would extend a helping hand to us when in need, I often contemplated running away from Darin to obtain freedom but could not succeed in my scheme. Now that an opportunity offered itself I availed myself of it and ran to Bahrein. I collected all the members of my family and placed them in a small jolly boat and came to Bahrein,. My masater and his men pursued us in another boat with a view to re-enslaving us but they did not succeed to reach us in our flight.

Now I request H.M's benign government to grant me, my wife, her mother ( ___________________) and her sister named ( __________________ ) and to my children Manumission Certificates and diving permits to enable us to dive and to earn our livelihood unders its protection as free born persons. For this act of magnanimity I shall be greteful for ever.

Faraj's mother tongue is Abysinian, by appearance is Abissinian and born in Abissinia.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

LIST OF THE MEMBERS OF FARAJ'S FAMILY WHO PRAY FOR MANUMISSION CERTIFICATES:

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

NAMES. AGE.

BRITISH GOVERNMENT

MANUMISSION CERTIFICATE

Be it known to all who may see this that the bearer Bakhit bin Ismail aged about 35 years has been manumitted and no one has a right to interfere with his /herliberty.

Dated: Bahrain this 18th day of December, 1943.

Signature and Designation of British Representative

Statement of Marzooq bin Saad aged about 35 years, recorded on the 3rd May 1927.

I bet to state that when a child of 13 years I was stolen by Abdullah bin Saif of Sohar while I was in Marindi at Zanzibar and was taken to Batinah where I was kept for a year. After the period of one year Abdullah bin Saif took me to Debai and sold me to Khamis bin Said. The latter kept me in service until now.

I was employed during these years in diving by Kahmis bin Saif who did not look after me well. He was making me to work hard for him but did not give me sufficient food and raiment. He often used to beat me and molest me. Now that I got an opportunity to run away from his serfdom, I ran away.

I did not like to go to Isa bin Abdul Latif as he takes money from slaves traders and men like my master and would burden me with heavy debts or he would create some other excuses for the retention of slaves like me with their masters.

I request the High Government to grant me a manumission certificate to enable me to work and earn my livelihood. 20-5-1927.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The applicant looks like an Abyssinian by appearance. His native tongue is arabic of Zanzibar. He wa born in Zanzibar.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Statement of 'Atiyah bint Mubarak, aged about 30 years, from Qatar, taken at the Political Agency, Bahrain.

I am originally a born slave. My father Mubarak and mother Za'afoor were brought from Yemen to Qatar when they were children. Actually I do not know the persons who brought them, but merely I heard from them. They were sold in Qatar to Ibrahim bin Salih _________. I was brought up in Ibrahim's house where I was married to Ibrahim's slave named Somaiman. The latter died about five years ago. One year after my husband's death I ran away from Qatar to Bahrain. On arrival here I did not report myself to Agency for manumission but I started to serve the people in Bahrain for two years and then I was engaged by Ni'mah _________ (P.C.L.) as a maid in his house. Now I have spent two years in the house. Ni'mah's family wants to proceed to Qatar on a visit and I want to accompany them. I shall be grateful if the Political Agent grants me a manumission certificate so that no one will interfere with my freedom at Qatar. I understand that my master Ibrahim died one year ago leaving seven sons, ________________________________ and ___________.

L.T.I. of Atiyah bint Mubarak

A.P.A.

A letter No. P/I.7/2142, dated 26-6-44 has been received from Mr. Packer (P.C.L.) regarding the above slave.

I have taken her statement which I submit herewith for sanction to issue her a manumission certificate. She is a slave from Qatar in case you want to submit it to P.A. for his approval please.

Statement of 'Idoh bin Mohammed (alias Sa'id bin Mohammed) slave of __________ of Qatar, taken at the Political Agency on 22-8-44, 30 years old.

I am originally a Balochi from Gwadur. I was brought from there by a slave-trader named Dad Kerim bin Abdul Kerim, to the Batinah coast and took me direct to Braimi. From there he took me to Dohah, Qatar, where he sold me to ____________________________ , for two rifles. I was then 8 years old. Husain above mentioned imprisoned me for one month thinking that I will run aways. I learnt Arabic stayed with them. Then he gave me a wife - a Balochi girl brought Mahmood ________ and bought by him - she gave birth to a son and a daughter. My son name Zayid, 6 years old, has accompanied me in my master's jollyboat which is now in Bahrain.

I request the High Government to give me and my son the freedom, because I have a large community scatterred in Muscat and Gwadur. I have a sister named Darroh married to one Challok working with Nasibkhan of Muscat.

L.T.I. of Idoh bin Mohammed

A.P.A.

The above slave states that when he speaks about his slavery to ___________, the latter says that he is free but refuses to grant him a document from his hand.

I suggest that the slave and his son may be allowed to stay in Bahrain to work for their maintenance. From his tongue it appears that he is of Balochi origin.

He will not be granted Manumission certificate, because in Bahrain he does not require any.

As regards __________, if he has any claim against him it is left to him to sue him if he wants please.

P.A. I agree if the slave (?) wishes to leave Bahrain he can be given M.C. at that time.

22.8.44.

Statement of Slave Mubarak bin Rozah, aged about 35 years, came from Qatar, taken at the Political Agency, Bahrain on 28-9-44.

My name is Mubarak bin Rozah. I am relating my name to my mother's because I do not know the name of my father nor the country from which I was brought to Qatar. I also do not know whether I was a born slave from slave parents or from free parents. I was too small, when I was brought to Qatar by the Bedouins, to recognize them, They sold me to one ______________, a Qatar subject. He died and I was transferred to his daughter Fatmah, who also died. So I have remained with her husband _________________, who is resident of Al Yumail, on the west of Aba Dhaloof. About 4 years ago I was married by him to one of his slave maids named Matroh. She gave birth to a daughter named Rozah. My master sold my wife and daughter to Sultan __________, who took my wife to Riyadh and sold her there. My daughter died at Qatar. I have been much ill treated by this master and I have no intention to return to Qatar. I ptay that I may be freed and allowed to remain at Bahrain. If I go back to Qatar, I will again be put into slavery, which I no longer like.

L.T.I. of Mubarak bin Roazah

A.P.A.

May grant him a manumission certificate and allow him to remain in Bahrain? He seems to be fit to work as a labourer please.

Issued m.c. No. 17 of 28-9-44

Statement of the slaves Bilal bin Faray and Hilal bin Faray, respectively aged 27 and and 25 years, from Qatar taken at the Political Agency, Bahrain on 1-11-44.

We are born slaves. As we heard from our parents that our father Faray and mother Si-deh _______ were imported from Yemen. We were brought up in the house of our parents' master Ahmed _____________, a diving nakhuda. Our parents died and also their master. The sons of the latter Ali and Amir took possession of the property of their father among which we were taken. Later Ali and Amir divided the property and each of them took one of us. I, Bilal, became the share of Ali and I, Hilal, under Amir. Since the last seven years their financial condition has weakened and we began to suffer from the trouble by them. We demanded from them to sell us but they refused. To escape from Qatar we managed to hire a canoe for Rs. 8/- to take us to Bahrain. Two days ago we arrived here and now we come to the Agency requesting to be monumitted.

L.T.I. of Bilal bin Faray L.T.I. of Hilal bin Faray

A.P.A.

The above two slaves state that they do not want to return to Qatar, but they propose to work at Bahrain or will join sailingcraft as sailors for abroad. They intend to make Bahrain their residence.

May grant them Manumission certificates and allow them to remain here for work please?

Yes. Issued m.c. No 19 of 1-11.44 to Bilal bin Faray

" " " 20 -too- Hilal bin Faray

Statement of Abdulla bin Mohamed aged about 25 years, recorded on 17th July 1927.

I beg to state that I was born at Mokalla. My father died when I was 9 years old. My mother Fatimah and two brothers Mubarak and Ali and a sister Ashya were alive when I left my native place. One day in the company of 4 others whose names were Mubarak, Saadullah, Hussain and Mubrook went to a place called Medi near Mokalla. We were, while on the way caught by fore by 15 Bedoins and were taken to Hejaz and Mecca and were all sold there. I was sold to one Abdul Azia of Shakara at Mecca for 1500 dollars. He brought me from there to Reaz in Nejd territory, and sold me to Hamaizi resident of Reaz. Hamaizi keeping me there for a few days took me to Hassa and from there to Qatar and sold me here Saleh bin Bakar. I have served this master for about 10 years as a diver and it is nearly 4 months now that owing to his illtreatments I have run away from him and have come to Bahrein. I request Your Honour to grant me a manumission certificate so that I may be a free man.

The man's native tongue is arabic and by apperance he looks an Abyssinian.

Statement of Jabaril bin Omar at present residing in the house of Hamdan bin Belal at Manama.

I, Jabaril bin Omar aged about 30 years was born at a place called Arash near Abha. When i was 14 years old my father died and my mother Fatimah and brother Ibrahim were alive when I left my native place. I had a coffee shop in the said village. One day when I was sitting in my coffee shop a quarrel arose among the Akhwans and I along with many others were caught and those Akhwans took us at different places. The man who caught me was Amfaraj bin Abu Asnin. He brought me by force to Hasa and sold me to Yahya bin Abdur Rehman, a resident of Qatar for Rs 600/-. Yahya from Hassa brought me to Qatar and re-sold me to Manah _______ of Jamel for Rs 1210/-. I served this master for six years and about 18 days ago my master came to Moharraq with his diving boat and wanted to return to Qatar. I ran away from his boat owing to his daily ill-treatment and came to Manama and pray that your honour will grant me a manumission certificate so that I may be a free man.

Statement of slave woman Khadia bint Mabrook aged about 35 years, recorded at the Political Agency Bahrain, on the 11th January, 1929.

I was born in East Africa. My parents were Swahilis but were not slaves. They were kidnapped and brought from East Africa to Nogher in Persia from where they were brought to Qatar and entered the service of the father of Abdul Aziz _____________. After the death of my parents I remained in the serivce of Abdul Aziz ___________. About 15 years ago he got me married with his slave Mabrook. I gave birth to two children, a son named Khairi 6 years of age and a daughter named Saidha 4 years of age. My husband died at the diving bank when my daughter was about 3 months old.

As my master's wife treated me with harshness and often beat me with sticks and as her big daughter hit me on the head with a stone and stuck me in the eye I managed to abscond from him and reached Bahrain by launch.

I have now come to enlist the Agency's help and request the British Government to issue me a manumission certificate so that I may lead a free life.

Statement of slave Marzook bin Belal at present staying in the house of Hamdan bin Belal at Manama.

I, Marzook bin Belal, aged about 30 years was born at a place called Sudan. I had six brothers. My father and mother were alive when I left my own country. When I was 11 years old I daily used to take away sheep outside to Sahra. One day it so happened when I was looking after sheep in desert a certain person Mohamad __________ resident of Takarneh caught hold of me and took away by force. to Jeddah and from Jeddah to Mecca where he sold me to a Turkish lady Aysha. I served her for 5 months when she re-sold me to Khalid _________. I served him for 6 years. Khalid ____________ again sold me to one ___________ of Shagrah to whom I served about 2 months and then he brought me to Hassa and sold me to Yahaha ____________. Yahaha brought me to Qatar and after keeping me for 15 days sold me to _____________ of Qatar. I served this master for 7 years. About 20 days ago my master ___________ came to Moharraq with his diving boat and wanted to go back to Qatar. Owing to his continuous ill-treatment I have absconded from Moharraq and came to the Agency for protection and pray your honour that I may be granted a manumission certificate so that I may be a free man.

Statement of the slave Rahmah bint Marzook, aged 45 years, taken at the Political Agency, Bahrain on 25th March 1944.

I am originally from Yaman. During the Wahhabi war in Yaman I was taken as booty. I was then a small girl and now I do not remember the name of my village. From there I was brought to Qatar via Riyadh and Hassa. At Qatar I was sold to Ibrahim ________________, now living _____________. Ibrahim's wife has been under treatment in the Mission Hospital for the last three months with whom I have come from Qatar.

In Qatar I was married to one Faraj _____________, slave of the above Ibrahim. He could escape and come to Bahrain for freedom. Now he is working as a policeman in the Bahrain State Police. Since my coming he has been visiting me in the Hospital. My husband is prepared to keep me in a house. I have left behind in Qatar my son ___________ of 12 years and my two daughters _________ and __________ of 16 and 15 years respectively. I pray to the High Government to call my above master and press him to arrange and bring my children from Qatar about whom I have got information that they are being maltreated by Majid bin Sultan, nephew of the above Ibrahim. These two men are living in the same house.

L.T.I. of Rahmah bint Marzooq

A.P.A.

The woman is here. I suggest that the above Ibrahim ____________ and her husband Faraj to be called for the first not to interfere with her and arrange to bring her children and the latter to identity her please. 25.3.44

as the owner of the woman and her children in Qatar is living in Moharraq, we can tell him to have the

Statement of Sa'id bin Husain from Qatar, aged about 35 years, taken at the Political Agency, Bahrain on 7-11-45.

My parents were free persons living at Madina (Hedjaz). I was kidnapped from them when I was 10 years old. I was brought by land to Kuwait, where I was sold to Salih Sulaiman ____________, of Qatar. My latter master brought me to Qatar and ever since I have been in his service. During summer I go to diving and in winter I work in the household. He used to give me very little money for my expenses. In the beginning he was treating me nicely and lately his treatment has been very bad, which fact has led me to run away. I, my wife Hasinah _______________ and my son ___________ walked from Dohah to the northern shore of Qatar where we joined a sailing boat as passengers for Bahrain. Now we have come to the Agency applying to be granted with manumission certificates.

L.T.I. of Said bin Husain

A.P.A.

The above slave states that he wants to live with his family in Bahrain, as such he may be granted a manumission certificate for them all. May grant him please?

m.c. No. 54 of 8-11-45 Yes ---

Statement of _________________, slave of ___________________ , now resident in Rafa, aged 35 years, taken at the Political Agency in Bahrain on 6th December 1942.

I was originally kidnapped from my parents Wadi Bal Jarshi, near Hedjaz by one Khobzan, when I was a small girl. He sold me to Ghalib bin Ali of Ghamid tribe camping on the western side of Ryadh. Ghalib died and his brother Khalid took me, who took me to Bisha on the western border of Hassa and sold me a slave trafficer name Ali of Shaqra (Nejd). This Ali took me to Hassa and sold me to Jalmood. The latter took me to Dohah and delivered me to one Isa bin Rabi'ah of al Kulaib tribe and slave trafficer. I remained with him two months after which he sold me to ___________________. I have now been with about 17 years. I am actually not a negro but white woman and ever since I could not be able to free myself from these Bedouins, otherwise I am tired of them and their ill treatment to me. When I came to _____________ house I was married to his slave, named Sa'id, who died 8 years ago. I gave birth to three daughters ___________________________.

My eldest daughter has been sold by my master to ______________ of Qatar for Rs 300/-. She is still alive. My other two daughters have been brought with me by my master to Barahin. I pray their manumission with me.

Statement of ______________(seond daughter of the above slave) aged 13 years old, taken in the Political Agency, Bahrain, on 6th December 1942.

I have been born and brought up in my master _________________'s house, so I like to remain with them at my own free will.

Statement of Johar bin Said of Qatar, aged about 35 years, taken down at the Political Agency, Bahrain, on 8th August, 1946.

I was born in the house of Sheikh ___________________ of Qatar in Qatar. I am a born slave. My parents were also slaves of the said master. My mother has been manumitted by my master. In summer I have been always working for him in pearl diving and my emoluments were taken by him. In winters I used to work for him in deserts. I have been ill-treated by him and have therefore come to the Political Agent, Bahrain, requesting to be granted a manumission certificate to enjoy freedom for the rest of my life.

L.T.I. of Johar bin Said

The move toward global abolition

By the end of the eighteenth century, European public opinion had begun to turn against the slave trade. In 1787, British Quackers formed the society for the Abolition of Slave Trade and petitioned parliament demanding its end. Most Western European countries abolished the slave trade in the first decades of the nineteenth century. In 1833, slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire. The founding of a republic in France in February 1848, followed three months later by a major slave revolt in the French colony of Martinique, led to the emancipation of enslaved people within the French Empire later that year. In 1897, Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed abolished slavery in Zanzibar which had become a British protectorate in 1890.

In the late-nineteenth century, the Horn of Africa, East Africa, Arabia and the Gulf were targets of antislavery campaign. The British concluded treaties with rulers in these regions. Among them were the Sultan of Zanzibar in 1873 and Khedive Ismail of Egypt in 1877. The British them implemented the Anglo-Ottoman Convention in 1880 and the Brussels act of 1890, both of which authorized the search of suspected slave ships and the arrest of slave traders.

But in Qatar and other Gulf states, slavery persisted well into the twentieth century. This partly can be explained by their dependence on enslaved labor for the production of exports like pearls and dates and the fact that the enslaved did not organize uprisings which would either force state negotiations of draw foreign attention to their plight.

By the early twentieth century, the British government tried to exert authority over Gulf waters as Ottoman power declined and Russian and rival European powers' interest grew in the region.

Forces leading to Qatari abolition

A combination of forces led to the abolition of slavery in Qatar. Some were external, exerted mainly by the British and the League of Nations. This diplomatic pressure resulted in a slow but steady retreat from slavery by Qatar and other Gulf States.

Other forces were internal. This had to do with Qatar's political modernization and changing economic fortunes with the discovery of oil and gas. The eventual ability to compensate slave owners meant that the system could end without political and social upheaval.Text of 1916 treaty between Great Britain and Sheikh Abdullah Bin Jassim Al Thani of Sheikh of Qatar, Dated the 3rd November 1916.

Whereas my grandfather, the late Shaikh Mohammed Bin Thani, signed an agreement on the 12th September 1868 engaging not to commit any breach of the Maritime Peace, and whereas these obligations to the British Government have devolved on me his successor in Qatar.

I, Shaikh Abdullah bin Jassim bin Thani, undertake that I will, as do the friendly Arab Shaikhs of Abu Dhabi, Dibai, Shargah, Ajman, Ras-ul-Khaimah and Umm-al-Qawain, cooperate with the High British Government in the suppression of slave trade and piracy and generally in the maintenance of the Maritime Peace.

To this end Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Percy Cox, Political Resident in the Persian Gulf, has favoured me with the Treaties and Engagements, entered into between the Shaikhs above mentioned and the High British Government, and I hereby declare that I will abide by the spirit and obligations of the aforesaid Treaties and Engagements.